TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT BERLIN, GERMANY

Course: Interdisciplinary Theory and Practice

TOPIC:

FOOD AND THE CITY: Opinion Paper and Reflection On Creating Urban Agricultural Systems: An Integrated Approach to Design by Gundula Proksch

written by Babatunde Oladogba

ABSTRACT

Cities have changed human interaction with nature and the more people move to reside in cities, the more increase in urbanization. The conceptual division between food and the city is probably one of the most prominent features of modernity as it became apparent as the population rises. Evidently, the rising need for food security, food production, and global circulation is creating awareness because of the high demand but low production and circulation, and it is also enabling people to dig into the possibilities of the urban agriculture system. This essay aligns my opinion and arguments on the topic of food and the city: creating urban agricultural systems with critical thinking as a planner on the rising issues in urban agriculture.

INTRODUCTION

The majority of the world’s population now lives in cities, and this population in urban areas will increase dramatically over the next 30 years (Craig et al, 2010, p.6). If in Latin America, already about 80 % of the population lives in cities, in Africa and Asia, the actual rates will double from 2000 by 2030 (Orsini et al, 2013). The growing urbanization can also be observed in the metropolis (cities with more than 1,000,000 inhabitants which were only 83 in 1950, and more than 400, with 21 Megalopolis (over 10,000,000 inhabitants) in 2006 (Orsini et al, 2013). It is foreseen now in 2020 that there will be at least 27 Megalopolis, out of which 13 in Asia, 6 in Latin America, 5 between Europe and North America, and 3 in Africa (Batty, 2008). Today, more than 53% of the world’s urban population now lives in cities of fewer than 500,000 inhabitants (UNHABITAT, 2008a). This urbanization process, however, has consequences in urban planning and as well brings a reduction of fertile lands, air, water pollution, and rising demands for food thereby creating a peri-urban area where the social-economic constraint is exalted and poverty is condensed (Baud, 2000). In this essay, I attempted to evaluate and juxtapose the current trend in urban agriculture taking food and the cities as the core topic.

MAIN BODY

Urban agriculture is part of the urban food system and it plays an important role in the urban food system. There have been several definitions of urban agriculture, but a simple definition by (Giseke et al, 2015, p.33) defines it as any form of formal or informal agricultural production in the city region.

This comprises primary and secondary agriculture, in which primary agriculture refers to land uses that are primarily focusing on the activities of agriculture whereas secondary agriculture comprises all land uses that integrate agricultural activities as an add-on to their primary land use including vertical farming, roof-top gardens on residential or commercial buildings and house gardens by (Giseke et al, 2015, p.34).

Today, urban food production has been seen for bringing multiple benefits. Food production in cities has a long tradition in many countries and the united nations development programme (UNDP) (1996) also estimated that urban agriculture produces between 15 and 20 percent of the world’s food. Urban agriculture, although practiced in both developed and developing economies, often serve different purposes, e.g. recreation in the former and food security in the latter, etc (Craig et al, p.10). We cannot then say Urban agriculture is a single entity as it comprises the locals, residual, farmland, small, community gardens, home gardens, reserves, greenhouse, roof garden, and so on. These various activities however share many opportunities and problems, which are distinctively different from the conditions encountered by rural agriculture (Eriksen-Hamel & Danso, 2010, p.86–93).

Gundula (2017) noted that urban agriculture is an interdisciplinary topic as it offers the opportunity for interdisciplinary work between architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning which I also agree with. Her article; Creating Urban Agricultural Systems: An Integrated Approach to Design documents the current state of urban agricultural design to inspire architects, landscape architects, urban planners, students, community groups, and interested residents in this growing movement. However, In my opinion, Gundula didn’t dwell much on challenges and problems that may arise in these alternative design approaches but rather extensively and successfully described the positivity and possibilities of the urban agricultural system.

When we look at the rising numbers of research activities and food becoming a priority in the policy councils today, only the urbanizing regions take the glory in respect of food circulation and consumption, while it is not coherence in the case of urban poor. Whereas, we cannot overlook or underestimate them as a larger percentage of urban food comes from the rural. In the case of an alternative growing system, it is arguable that the technology required to facilitate food production in the urban agriculture system as indicated by Gundula (2017) is yet to circulate across the world since most of the projects discussed in the article only addressed few continents. However, without raising proper awareness, only a few would continuously benefit from these developments while the urban poor continues to grow food in a primeval way.

Urban poor on the other hand are most likely to experience food market instability because most of the urban poor spend a large proportion of their family income on food. It was estimated by the Asian Development Bank that 60 percent of all income of the poor in Asia is spent on food and in the city of Dar Es Salaam, the amount is 80–85 percent (Craig et al, 2010, p.8). Comparing this with the case of Canada and that of the United States, the proportion varies from 6 to 15 percent. Therefore, it is clear that there is a small change in the price of basic foods which can lead to a significant increase in hunger. The vulnerability of city residents is aggravated by two things highlighted by the Food and agricultural organization (FAO). First, urban food is more dependent on tradable commodities and traditional means of sustenance, second, there is less land owned by residents on which to grow their food for sustenance. In cities, the high cost of real estate has pushed many of the poor and recent migrants to the margins. They are forced to settle on polluted lands where they sometimes produce food with certain health risks (Craig et al, 2010, p.8). The people however do not have orientation or access to most of these new systems of urban agriculture. As such, some still manage to survive by traditional methods of farming.

A clear example was presented by the community solution (2006) in the video documentary Lecture 10a stating the power of Community and How Cuba Survived Peak Oil. It was noted that the breakup of the sovereignty union in early 1990 created a major economic crisis in Cuba. They lost 80% of export and import, factories closed, buses stopped running, electrical blackouts and food were scarce, people almost starved. Over the following decade, Cuba took a drastic step to find a solution, Cuba adopted a green revolution and extensively practiced urban agriculture. During this period, a lot of people started farming, urban agriculture was promoted, people cooperated and cared for one another. More also, for them to increase food production, the government worked with farmers to find local solutions that brought about land distribution as seen in fig 1 below. All these helped them to survive the crisis (community solution, 2006).

Fig. 1: Picture showing a local farmer harvesting production during the Cuba crisis, Source: Community solution,2006)

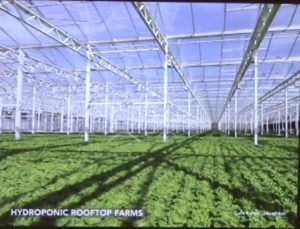

Most of the case studies of urban farming presented by Gundula (2017) use new technology; one example is the LUFA farms hydroponic rooftop farms, which were presented as one of the case studies in Gundula’s lecture. It is one of the biggest typologies of urban farming, and it is located in Montreal, Canada, and uses high-level technology.

Fig. 2: Picture showing a LUFA farms hydroponic rooftop farm in Montreal Canada, Source: creating urban agricultural systems lecture, Gundula Jan. 2018)

While we anticipate the future and explore different possibilities for an integrated urban agricultural system, it is as well important to know that the paramount issue regarding the sustainability of urban agriculture also revolves around how to protect urban land for green space and food production. Thereby highlighting the challenge involves in governance, legal issues, and the question of how to create sustainable market economies among communities and cities (Craig et al, 2010, p.9). The need for implementation on the protection of open space within cities, accepting agriculture as legitimate land use, promoting and maintaining food markets, and establishing food policy councils to coordinate municipal responses to urban food security (Craig et al, 2010, p.9). It is also interesting to know that civil society is founding food policy councils worldwide and policymakers are supporting it, one example of this implementation is the Milan Urban Food Policy pact which is an international pact signed by 209 cities including berlin from all over the world (Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, 2015, p.2). Gundula also acknowledged this policy movement on the fact that due to a broad set of concerns that urban agriculture projects try to address such as food security, community support, climate change, and economic development, food policy advisory councils (FPCs) and private advocacy groups have become important activists for new land-use planning and policymaking (Gundula, 2017).

Even though we appreciate innovative technology, we still have to somehow question the disadvantages that come with it and find possible solutions. Gundula admitted that realizing large-scale BIA projects like the Lufa Farm in fig 2 above comes with an enormous hurdle. The challenges that come with it vary depending on the budget, scale, location, and primary goals. When we look at urban agriculture growing methods and approaches described by Gundula such as hydroponics, anaerobic to mention but few. This system use technology to reduce resource inputs, increase water and nutrient efficiency, and increase productivity. Anaerobic digestion on the other hand utilizes biodegradable waste to produce energy in an anaerobic digester, a vessel that works like a mechanical stomach. Anaerobic bacteria convert organic matter into biogas and digestate in the absence of oxygen. With all these, we see the advantages these methods bring to urban agriculture, however, the disadvantages that come with the use of these methods are not discussed in detail.

CONCLUSION

Urban agriculture has become a global trend, and it is continuously expanding across the world. It is becoming a measure to expand access to locally grown food and a means of engaging the public to the many aspects of urban food systems that we have lost (Nikola, 2018). How food grows, what grows regionally and seasonally are all important lessons in creating a better-informed urban consumer (Nikola, 2018).

Interestingly, policy implementations are ongoing across different countries on food security, land management, and distribution for green space and food production, however, there is a need to raise more awareness.

It is clearer that many growing systems have been tested and have been proven efficient and reliable, however, some of them require a high level of technology to run efficiently. In the context of urban agriculture systems, most of the case studies described by Gundula in her lecture operate on a small scale, and to advance in a meaningful way, there is a need for large-scale urban agriculture.

Architects and design professionals plays important role in these system developments. While urban agriculture can enrich architecture and its allied design professions, proper education and awareness need to be extended to the locals. Promising solutions need to be put in place in addressing the challenges in urban agriculture. Thus, by understanding its synergies, design professionals can integrate into large-scale urban farming.

REFERENCES

– Batty, M. (2008). The size, scale, and shape of cities. Science 319:769–771. doi:10.1126/science.1151419

– Baud, I. (2000). Collective action, enablement, and partnership: issues in urban development.

– Community solution (2006). The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhfpmKAEfy4/ [Accessed: 20 August 2020].

– Craig J. P., Saral P. & Jules P. O. (2010). Urban agriculture: diverse activities and benefits for city society.

– Eriksen H. N. & George D. (2010). Agronomic considerations for urban agriculture in southern cities, p.86-93.

– Giseke, U., Maria G., Matthias K., & Dieter S. (2015). Urban Agriculture for Growing City Regions: Connecting Urban-Rural Sphères in casabanca

– Gundula P. (2017). Creating Urban Agricultural Systems: An integrated approach to design.

– Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (2015). Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. Available at: http://www. milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/ [Accessed 18 August 2020].

– Nikola T. (2018). Urban farming: 3 examples to implement this new trend. Available at: https://www.geoplastglobal.com/en/insights/urban-farming-3-examples-implement-new-trend/#:~:text=by%20Nikola%20Tosic%2C%205%20February,and%20is%20continuing%20to%20grow.&text=How%20food%20grows%2C%20what%20grows,a%20better%20informed%20urban%20consumer.

– Orsini F., Remi K., Remi N., & Giorgio G. (2013). Urban agriculture in the developing world: A review.

– UNDP (1996). Urban Agriculture: A Neglected Resource for Food, Jobs and Sustainable Cities, UNDP, New York.

– UN-HABITAT (2008a). State of the world’s cities 2008/09. Earthscan, London.

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig. 1: Picture showing a local famer harvesting production during the Cuba crisis,

The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil (2006). Available at: https://www.filmsforaction.org/watch/the-power-of-community-how-cuba-survived-peak-oil-2006/ [Accessed: 20 August 2020].

Fig. 2: Picture showing a LUFA farms hydroponic rooftop farm in Montreal Canada,

Gundula P. (2018). Creating urban agricultural systems lecture Available at: https://vimeo.com/253001157 [Accessed: 20 August 2020].